Good old British Burgundy

"He suggests that this English taste may be some form of perversion, like our national taste for being whipped."

In 1966, The Sunday Times1 ran an investigation into dodgy practices at British wine merchants. One company based in Ipswich turned out Beaujolais, Nuits-Saint-Georges, and Châteauneuf-du-Pape made from two table wines blended in different proportions. It caused a scandal among readers but much of the wine trade shrugged its shoulders as such behaviour was far from unusual.

Usually what was being sold as Burgundy in Britain was what the French called "soup." In other words, a concoction that at best would be some decent Burgundy beefed up with wines from the Rhône or Algeria and, at worst, wouldn't contain any Burgundy at all. British Burgundy was usually closer to Châteauneuf-du-Pape than the delicate, fragrant wine that we know today.

Before Britain entered the Common Market such wines were entirely legal. The words on a bottle like Beaune, Volnay, or Nuits-Saint-Georges were more about the style than its place of origin. We might look at this as the bad old days of wine, but many drinkers preferred the old-school wines. New Zealand wine journalist Don Hewitson writes of:

"reasonably priced, attractive, rich and luscious burgundies. A dinner-time bottle of commonplace Côte de Beaune-Villages would ease the worries of the business day: now all a similar bottle does is make me annoyed (at the thinness and lack of fruit)."

The problem was exacerbated by how Burgundian vineyard practices changed in the '70s and '80s, with new, more efficient clones of pinot noir planted and the use of synthetic fertilizer that boosted output at the expense of flavor. Combine that with some atrocious vintages and you have the recipe for some feeble, overpriced wines. No wonder some longed for the good old Burgundy. I still remember crustier members of my father’s wine club muttering about how Burgundy wasn’t what it once was.

Hewitson is quoted by Auberon Waugh, another lover of old-timey wines, in his article ‘Burgundy Now and Then.’2 Waugh explains how beefy Burgundy was the creation of Jean-Antoine Chaptal, the scientist and Napoleonic government minister who gave his name to the technique of adding sugar to wine to boost alcohol levels—chaptalisation. Waugh writes:

"Chaptal... permitted the addition of sugar and boiling must and prescribed a weighted cover on floating grape skins in the vat to allow maximum infusion of tannin—the recipe for a slow-maturing wine of great density. They were also interpreted to allow the 'beefing up' of these vintages by addition of coarse young Rhône or Midi wines... It was these practices which produced, year after year, the splendid wines which Don Hewitson remembers..."

Similar things used to go on with Bordeaux. The wine would have been mixed by merchants in the city of Bordeaux with heavier wines to make it more palatable to English tastes. The Victorian wine expert Cyrus Redding wrote: "it has been thought necessary to give pure Bordeaux growths a resemblance to the wines of Portugal... Bordeaux wine in England and in Bordeaux scarcely resemble each other."

If you were lucky, your Château Palmer might contain a good dose of Hermitage from the Rhône and if not, brandy and elderberries. You can actually buy a wine today from Château Palmer called "Historical XIXth Century" which contains 10% Hermitage.

It turns out that Australian cabernet-shiraz has a noble parentage. When we laugh at how Australians or Americans used to call their robust grenache and other Southern grape-dominated wines Burgundy, we are missing the point—this is the sort of Burgundy they were used to.

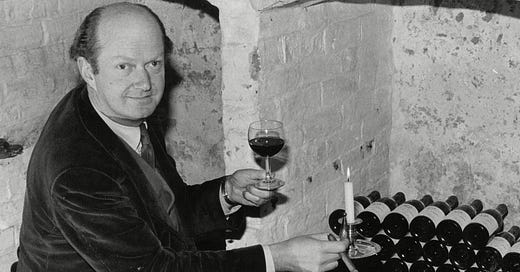

Waugh writes: "He (Burgundy expert Anthony Hanson) suggests that this English taste may be some form of perversion, like our national taste for being whipped." The only way to find wines Waugh liked was to buy things described by wine merchants as "almost sweet," "old style," "concentrated," or "dark." Or try to hunt out old bottlings from Averys, the Bristol wine merchant that was famous for its traditional wines.

I've often been curious: what would these wines have tasted like? I could find some British-bottled wine like a 1961 Beaune Clos du Roy Maison Doudet Naudin from Berry Bros. Or I could try to make my own.

The Auberon Waugh Burgundy challenge

I was thinking of using some very light supermarket Burgundy, but I recalled that Waugh's wines started out beefy before being further beefed up. Then I remembered I had some Chorey-lès-Beaune Les Beaumonts 2020 from Jean-Claude Boisset, which was a bit foursquare and had no shortage of alcohol at 14.5%. The beefing would be done with some Cairanne, mainly Grenache, from Aldi. Waugh recommended keeping them for at least ten years, but I don't have time to do that.

What would it be like if I mixed them together? But also, what ratio would you put them in? The results will amaze you.

I invited my neighbour Gary Harrison round, who has a WSET Level 3. We conducted things under less than scientific conditions, having had a bottle of crémant and a half bottle of phenomenally good Calon-Ségur 1996 before we started.

I made up three cuvées: starting with 10% Rhône combined with 90% Burgundy, then 20% Rhône/80% Burgundy, and went up to 30% Rhône to 70% Burgundy. We also tasted the Burgundy on its own. And the results?

As I mentioned, the Chorey-lès-Beaune is not the most elegant of wines, being tannic, dark and spicy. I am not sure I would recognise it as pinot noir on first sniff. Adding the Rhône to it did it no favours, obliterating any trace of perfume and making it taste chunkier and more tannic. The 30% Rhône was actually quite pleasant, but only because the southern wine was fairly dominant by this stage. The mixture that worked best was the lowest one, but we unanimously preferred the neat Burgundy.

I think using a lighter Burgundy would see a similar effect, with the wine totally overwhelmed by the Rhône. Auberon Waugh recommended keeping his soup Burgundies for at least ten years, so perhaps some sort of magical alchemy would happen in the meantime. As for my rather unlovely Chorey-lès-Beaune, I wonder if time would allow it to emerge as a beautiful swan.

As recorded in Andrew Barr’s Wine Snobbery.

From Waugh on Wine sent to me by super subscriber Curate’s Egg.

Allegedly what Avery's used to do was to add a bottle or two of vintage (of course) port to every barrel of Burgundy to beef it up. Being a born and bred Bristolian I have drunk quite a few of their bottlings from the 1960s and 70s and can well believe it. They were soupy farmyardy and bretty.

I enjoyed them and actually rather miss them.

Our first vintage in the Languedoc, 1994, we attempted to make a VDP wine that would please our burgundy-phile palates from what raw materials we had. We found a blend of approximately 60% Merlot, 25-30% Carignan and 10-15% Cinsault had the freshness (from Carignan) and elegance (from the Cinsault) to balance the strength and ripeness of the Merlot.

But we didn't have the finances (and courage) to bottle the whole cuvée and we sold off most of it in bulk. When we were loading the tanker I noticed that the delivery address was in Aloxe Corton. In 1994 there were only 2 negotiants in Aloxe Corton and both made exclusively "Grand Vin de Bourgogne".

I'd like to think that Don Hewittson would have been happy with their 1994s.