I Regret Almost Everything - Keith McNally

A review of the autobiography of 'The Restaurateur Who Invented Downtown.'

Harvey Weinstein has a memorable walk-on role in I Regret Almost Everything by Keith McNally. Taking a break from being New York’s most celebrated restaurateur, McNally wrote and directed a film called End of the Night that was showing at Cannes in 1990. Its auteur hoped that Weinstein, whose picture Sex, Lies and Videotape won the Palme D’Or the previous year, would distribute it. The big man is blunt: “I didn’t like your film and I’m not going to buy it” and then continues “but I’d still like to come to the after-party”.

McNally admires Weinstein’s honesty, if not much else, so I’m going to be straight: I didn’t enjoy I Regret Almost Everything. Which is a shame because the raw materials are promising: he was born poor in Bethnal Green to a highly-strung mother who treated McNally’s father, a dock worker, as beneath her. One of four children, his brothers were the toughest boys in school but Keith McNally had a gentler disposition.

He briefly became an actor and appeared with John Gielgud in Alan Bennett’s 40 Years On. His mother worried about him working in the theatre because “John Gielgud’s homosexual!” Her worries were well-founded as a young McNally had an affair, not with Gielgud but Bennett - something that I am sure will be all over the tabloids by the time this review comes out. Despite support from Bennett and Beyond the Fringe colleague Jonathan Miller, his career never really takes off. During the audition for one of the droogs in A Clockwork Orange “I saw Kubrick roll his eyes”, McNally remembers. He didn’t get the part.

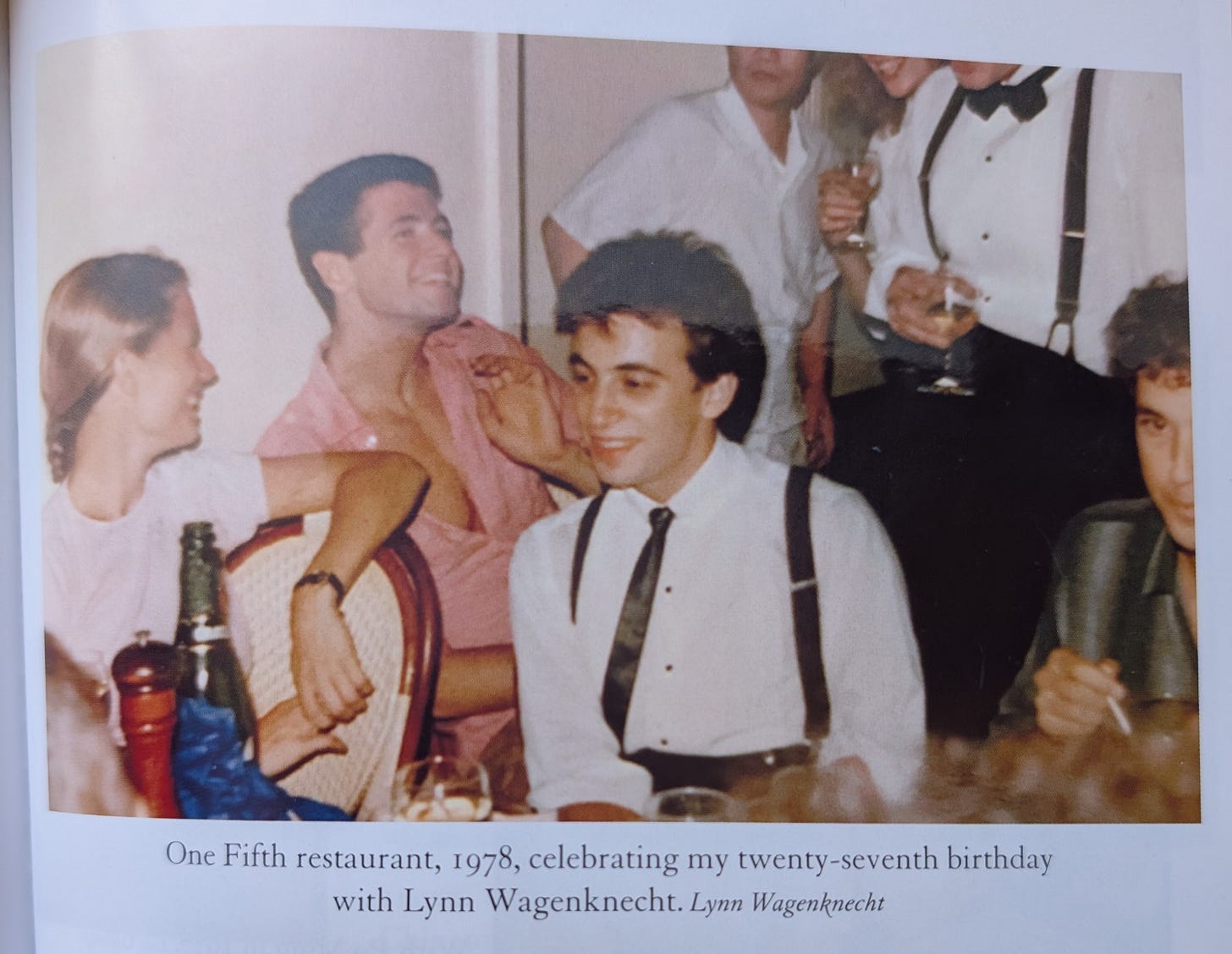

In the mid Seventies, the 24-year-old McNally moved to New York with dreams of becoming a writer but instead he got a job as a waiter. From there he opened his own place, Odeon, with his brother Brian and first wife Lynn Wagenknecht, and it became the cult restaurant of the 1980s. The New York Times hailed him as "The Restaurateur Who Invented Downtown." Regulars included John Belushi who would turn up at 3am after recording Saturday Night Live, his friend Anna Wintour, another Brit who made it big in Manhattan, and the author Jay McInerney, who set much of his debut Bright Lights, Big City there. McNally said of the novel “my instinct told me the book was going to be a turkey” so it’s sporting that McInerney has provided a laudatory cover quote for I Regret Almost Everything.

This giddy run of success continued with restaurants including the Parisian-influenced bistro Balthazar, founded in 1997 and still going strong today, and a nightclub called Nell’s where McNally once refused to let Madonna off the $5 door charge, after which she lambasted him as a “fucking bastard.” Another, happier night saw Prince play an impromptu two-hour set. Ah, the Eighties.

McNally was the king of New York but he never seemed to be enjoying himself: “I’d often stand silently on the edge of the dancefloor, spellbound by the dancers and envious of the ease with which they abandoned themselves”. There was no cocaine and Stoli on the rocks for him. As the only sober one in 1980s Manhattan you would expect him to be the perfect person, the insider’s outsider, to document this heady time. But you would be wrong. McNally has a rare gift for the non-anecdote. At one point he befriends one of Picasso’s ex-girlfriends and then writes: “unfortunately, I was so captivated by Gilot’s expressive, birdlike face that I didn’t take her stories in and, as a consequence, have no memory of them.” Thanks Keith!

I kept writing “thanks Keith!” in the margins of my proof copy because he is the master of the non-sequitur and extraneous detail. An otherwise interesting aside about New York’s arthouse cinemas segues into a whole paragraph listing his favorite films of the 1970s, only to conclude with him telling us that he has never seen Star Wars. The other thing I kept writing was, “why is he telling us this?” There’s one bit where he lists notable people who are left-handed. There are constant references to authors he has read but his engagement with them rarely rises above the sophomoric. Pride and Prejudice is “a masterpiece” and, when he comes to Graham Greene, he says “The Quiet American was my favourite, and still is”. He does not explain why.

McNally is “repulsed by clichés” yet the book is full of them. Istanbul has “mysterious domes and minarets”. Jonathan Miller is described as a “true polymath” and a “genius”. Robert Hughes was a “genuine intellectual” and Christopher Hitchens had a “formidable intellect”. He went to see Timon of Athens at the National Theatre with David Hare and Tom Stoppard, “two of the most brilliant playwrights of the past half century”. This just isn’t good enough. It reads like a first draft, a good editor would remove the banalities and encourage McNally to develop the promising stories.

One thing he does remember is criticism of his restaurants. He recalls, sounding fabulously petty, that Mimi Sheraton from the New York Times reviewed 71 restaurants in 1980 and despite only giving it one star the “Odeon is one of eight that remain open today”. When Balthazar’s London outpost is given a pasting, he writes:

‘It wasn’t the criticism of the food that most bothered me. It was the reviewer’s desperation to be funny. W. H. Auden said “One cannot review a bad book without showing off”, This is also true of London restaurant critics. In particular the minuscule journalist Giles Coren (“Not a memorable mouthful to be had. Like all New York restaurants”)’.

Keith, let it go. Like many people who are extremely successful in one field, McNally was dissatisfied and wanted to fulfill his old dream of being a writer and director hence the film End of the Night and its follow-up Far from Berlin. To his credit, McNally has the self-awareness to know that his films were no good. “Real writers write stories they have a connection to. Fake writers write stories about Berlin,” he says.

One of the frustrating things about McNally’s writing are the occasional sparks of what could have been. His encounter with a landlord called Bill Gottlieb who he was trying to rent a space off in the meatpacking district is one of the best things in the book:

“Gottlieb owned around a hundred properties in downtown Manhattan and was known as an eccentric. Though a billionaire, he dressed like a slob and carried all his important papers in a shopping bag. Gottlieb supposedly trusted no one and in his pockets carried all the keys to his many buildings. Gottlieb asked me what I wanted. I told him I wanted to build a restaurant in one of his empty spaces. He didn’t respond. I said I had a lot of restaurant experience; I owned Balthazar. “I don’t care what you own!” he screamed. “Can you cook?” “A little.” “Cook me dinner at your place next Wednesday.”

The otherwise forgotten Gottlieb springs off the page in pungent detail. Why couldn’t McNally write like this about Christopher Hitchens or Bennett?I was expecting bitchiness, and on the relatively few occasions that McNally lets himself go, the book comes to life. I relished his description of the “coiffured businessman turned restaurateur Richard Caring” in the London branch of Balthazar: “Caring knew precious little about restaurants, but a whole lot about shafting people.” And he has a well-aimed dig at his nemesis Nobu boss Drew Nieporent, who boasts of his connections to Robert de Niro even while the two men are hospitalized together. Call me shallow, but this should have been the meat of the book.

Instead, much of the narrative focuses on McNally’s incapacitating stroke and subsequent suicide attempt. The very first line is “In early August 2018, I tried to commit suicide.” His second wife Alina left him, and he was estranged from his children from that marriage, George and Alice. Although his writing is honest, — nearly unreadably so at times — the editorial light-touch means that there are moments of inadvertent levity for those with childish minds:

“In my third week at McLean, I received a highly sympathetic letter from Alan Bennett suggesting that I “write things down.” That was Alan’s understated way of encouraging me to write about my suicide attempt. He often used the tradesman’s entrance to discuss weighty topics.”

The book’s title is at least apt. On this evidence, McNally is a man consumed with regret. There’s the time he didn’t visit his daughter from his first marriage when she was in a clinic for depression. Or when his mother visits from England and he largely ignores her despite repeatedly promising to show her the town he is the toast of. It takes guts to admit he has been a terrible husband, father and son but the pervasive self-loathing on display here means that the author is lousy company over 300 pages.

It’s a shame because McNally really has had a remarkable life. He’s become close to interesting and famous people, been the toast of Manhattan and known utter despair, often at the same time. He had a ringside seat at two of the greatest cultural scenes of the 20th century, Sixties London and Eighties New York, and continues to run restaurants today, offering titbits of their day-to-day operations via his engaging Instagram account. What would a novelist like William Boyd have done with such a story? Sadly we’re stuck with McNally’s version for the time being. I’m waiting for the unauthorised no-holds-barred biography. That should be worth reading.

A slightly different version of this appeared in The Spectator World.

‘Thanks, Keith’ (enjoyed this review)

Great review!