'A Most Noble Water' - the real history of gin

Everything you thought you knew about the history of gin is wrong, claims a new book.

Drink history can be confusing and murky, perhaps because it involves alcohol. With say the motorcar we can point at Karl Benz or Gottlieb Daimler but nobody really invented the dry martini.

This is why people who write about drink history like to jump on little certainties like dates or historical figures even if they’re not quite as stable as they first seem. Examples would be Dom Perignon invented champagne (almost certainly not true) or his rival Christopher Merret in England (truer but only up to a point). I’m as guilty of this as anyone. One of the big dates in drink history is 1688 which is when gin arrived on these shores when William and Mary took the English throne in the so-called Glorious Revolution.

William of Orange was a Dutchman and brought with him a taste of geneva - a juniper-flavoured spirit popular in the Netherlands. Gin was around before this date but generally it was thought to have originated when English volunteers went out to fight the Spanish in the Netherlands. Either way there was a Dutch connection.

Not so fast, says husband and wife duo Anistatia Miller and Jared Brown in A Most Noble Water: Revisiting the Origins of English Gin. She’s an academic historian and he’s a master distiller, founder of Sipsmith, and I met him a couple of years ago at a Sipsmith event and as soon as we got onto our shared favourite topic, it very quickly became clear that he knew far more about the history of gin and indeed drink than I do.

One of the reasons why I am nervous about being called a historian is that I don’t do any real history, which I think of as uncovering dusty tomes and reading them while wearing white gloves. I just read books and attempt to turn other people’s research into an amusing narrative. Brown and Miller, however, have done things properly. They have actually delved into archives for primary sources and what they have discovered should rock the drinks world to its foundations.

According to the authors gin almost certainly came from Germany, a recipe for gin was translated into English from German in 1527. The book shows how juniper-flavoured spirits were being enjoyed in the reigns of Henry VIII and Elizabeth I, long before the Glorious Revolution. Furthermore they uncovered a recipe in a manual at the Worshipful Company of Distillers of London from 1639 which closely mirrors the flavour of modern gin which Sipsmith has put into production - and very good it is too.

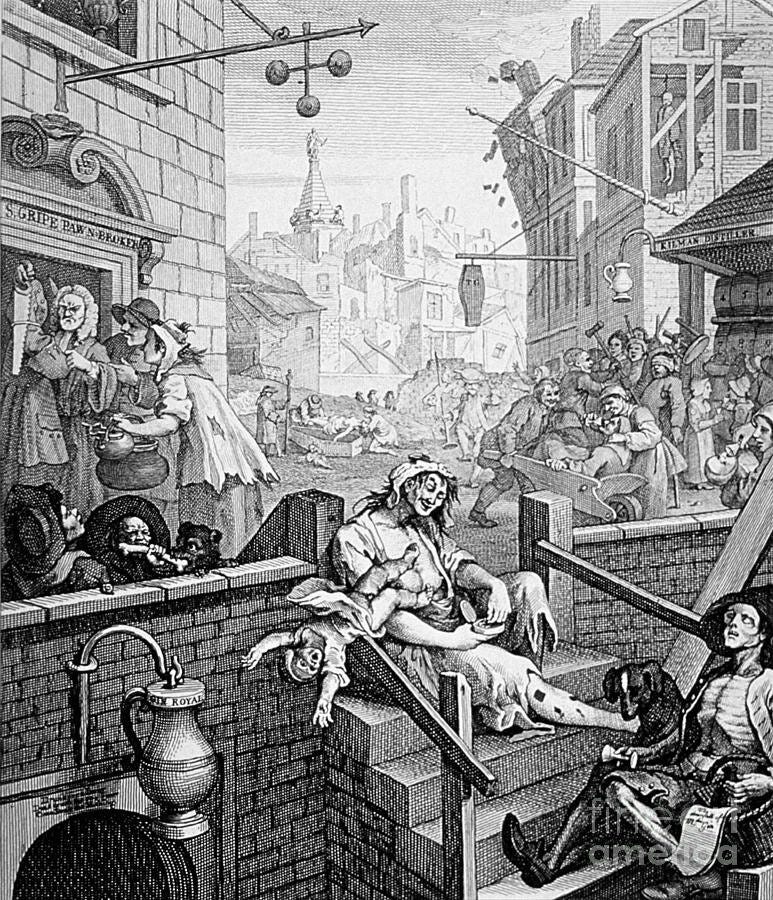

Not only this but the fearsome truth-seeking duo also take issue with the whole concept of the ‘gin craze’ immortalised in Hogarth’s ‘Gin Lane.’ I wouldn’t go as far as they do in describing it as “tabloid puffery” but their argument that gin took the rap for a dramatic increase in alcohol consumption and drunkenness across Georgian England when there were other drinks to blame such as port, cider and strong beers like porter is convincing.

In this chapter they also look at the various so-called ‘gin acts’ which were designed to regulate alcohol consumption in a detail that I’ve never seen before in a drink book. It’s incredibly impressive, if sometimes quite hard to follow, at least for me. The book can be an uncompromising read at times. I will admit that I had to email the authors to clarify certain things.

There’s more disassembling of canards later in the book. According to them “no one in the history of tonic water ever drank it as an antimalarial. That was made up by a sloppy drinks writer sometime around the 1970s, and has been echoed ever since”. Guilty as charged. Tonic water was a loose term for a supposedly health giving tonic. Some would have contained quinine though, the authors argue, not to treat malaria but digestive ailments.

Cleverly the book doesn’t cover the development of the cocktail in America and the ebbs and flows of gin since then leaving room for a sequel. “But that, dear reader,” they write “is a story of another day.”

Despite occasionally being hard to follow, this book deserves classic status, and its flaws can be explained by the sheer volume of research crammed into under 300 pages. The bibliography alone means that they have done the hard work for lesser writers. All I can say is thank you.

There was a good In Our Time about the gin craze. I assume they were just necking it like pirates back then but now gin must be the only spirit that people would never normally consider drinking neat. Who does that? Even the driest martini needs a little vermouth.

Well they might know a lot about gin,but not so much about art and politics.Hogarth’s Gin Lane has to be seen alongside his Beer Street.

Learn how a pair of engravings by satirical artist William Hogarth were used to alter the drinking habits of the British public in the 18th century.

Made to support the government's Gin Act of 1751, William Hogarth's exaggerated engravings warn of the dangers of gin consumption while extolling the benefits of beer drinking.

The government realised that gin drinking could not be eradicated ,so it had to be replaced with Beer which was much lower in alcohol and better for moderation.

Beer Street shows people as healthy and industrious and engaging in enjoyable flirting.

I recommend viewing the terrific Rake’s Progress in Sir John Soane’s museum in London to see a great artist using a story board of eight pictures to tell the perils of mixing alcohol with gambling ,affairs and prostitutes with the unhappy ending of the middle class to live like aristocrats.